DIAGRAMS

[ PDF Viewer ] | [ Diagrams ] | [ Judgement ]

Taher Fakhruddin Saheb alias Taherbhai K Qutbuddin alias Taher Bhai Qutubuddin

Plaintiff

Aged 47 years, Indian Inhabitant, residing at Fourth Floor, Flat 1, Al-Azhar, Saify Mahal, Malabar Hill, A.G. Bell Road, Mumbai 400 006 and having a residence at Darus Sakina (Madhuban Bungalow), Pokharan Road Number 1, Upvan, Thane (W) 400 606

~ versus ~

Mufaddal Burhanuddin Saifuddin,

Defendant

Aged 67 years, Indian Inhabitant, residing at Burhani Manzil, 2nd Floor, Saify Mahal, Malabar Hill, A.G. Bell Road, Mumbai 400 006

Page 1 of 226

23rd April 2024

APPEARANCES

For The Plaintiff

Mr Anand Desai, Advocate

With: Chirag Mody, Nausher Kohli, Samit Shukla, Saloni Shah & Shivani Khanwilkar, Advocates

i/b DSK Legal

For The Defendant

Mr IM Chagla, Senior Advocate Mr JD Dwarkadas, Senior Advocate Mr FE DeVitre, Senior Advocate Mr Pankaj Savant, Senior Advocate Mr Firdosh Pooniwalla, Senior Advocate

With: Azmin Irani, Abeezar Faizullabhoy, Shahen Pradhan, Murtaza Kachwalla, Jehaan Mehta, Ammar Faizullabhoy, Chirag Kamdar, Juzer Shakir, Jaisha Sabavala & Mustafa Maimoon, Advocates

i/b Argus Partners

CORAM: GS PATEL J

JUDGMENT RESERVED: 5TH APRIL 2023

JUDGMENT PRONOUNCED: 23RD APRIL 2023

JUDGMENT

General Background

1.

By any measure, ten years is a very long time for a lawsuit to come to final judgment. But this case is not just about the time it took. Voluminous pleadings, over ten thousand documents of various description including historical texts going back several centuries, nearly a dozen witnesses with depositions of many thousands of questions and pages, and arguments that, even in a severely curtailed form ran for over a month, all ensured a prolonged trial. In our court, this case is perhaps unique that it began and ended with one judge (and, to put it more piquantly, of the judgeship itself almost beginning and certainly ending with the case) rather than passing from one judge to another. The Plaintiff's evidence was completed in court itself, not before a commissioner for recording evidence, which, too, is fairly unusual. So was some of the Defendant's evidence. The rest went to a commissioner. Then came the business of sorting through that evidence.

2.

By then, the documents that had been compiled had run through an utterly extraordinary discovery and inspection process that included multimedia (audio and video both, plus photographs). There were compilations of compilations, and some of the titles of these multi-volume compilations bordered on the bizarre.

3.

Covid and the pandemic lockdown interrupted the until then fairly orderly progress in the trial. Technology came to the rescue and the contesting parties and I were able to complete a portion of the trial during the lockdown by deploying some unusually sophisticated internet links: the witnesses were in London, the lawyers were scattered across Mumbai, my staff and I were in the High Court. We had two parallel high-speed internet lines, one for the actual cross-examination and the other linked to the real-time transcript so that everyone could see the questions and answers being recorded. The entirety of the evidence is in question and answer form.

4.

By the time final arguments began, the record had ballooned out of all proportion. By agreement, everyone moved to a digital, soft-copy version with appropriate hyperlinks to the digitized record. The level of assistance in the technology, apart from the formidable forensic skills, must be commended. Without it, this was not possible.

5.

Yet, the issues are only five. Their impact is, however, much more profound. Leaving aside the more mundane issues such as maintainability, the central issues will affect a community across the globe. For this reason, from the beginning, I ensured open access both in the court hall itself and also online through the hybrid video-conferencing option. The hearings were open to all. During the final arguments, attendance ran to several hundred people online. Except for one minor kerfuffle with a newspaper, there was no untoward incident.

What the case is about

6.

In a word: control. Control not of property, despite the wording of some reliefs in the plaint, but the kind of control that is both invasive and pervasive - control over the entirety of a particular faith, and, with it, of a way of life. It is not a case only about jockeying for a particular position (let alone a rank). This is entirely because of the nature of the position in question within the faith - it is, as we shall see, not just of the order of a papacy in terms of numbers and adoration, but something far more profound; and accepted as such. Of the leader of the Dawoodi Bohra faith, the Dai al-Mutlaq or Dai or the Syedna, there is an acceptance of utter infallibility, even of divinity (or as close to it as a mortal may get), and an absolute commitment to the Dai's complete authority at the most personal and intimate levels.

7.

The 52nd Dai in line, Syedna Mohammed Burhanuddin Saheb, died on 17th January 2014. The Defendant said he had been appointed - I use this word loosely at this stage; it is at the heart of the suit - the successor, the 53rd Dai. The original Plaintiff, the present Plaintiff's father, Khuzemabhai Qutbuddin, brought suit. He claimed it was he, not the Defendant, who was the rightful successor. He had, he said, been so appointed decades earlier.

8.

The faith split. Each rival had his own followers. After Khuzemabhai died - his evidence was taken in Court - his son, Taherbhai Qutbuddin, stepped in (as his father's appointed successor). Nothing turns on this amendment, so I will rid myself of

it immediately: the application for amendment was opposed saying that the suit had abated, but I allowed the amendment. The Defendant did not appeal. The suit went to trial with the amendment and Taherbhai Qutbuddin as the Plaintiff.

9.

I will turn to the prayers presently, but it was clear from the start, when an application for interim relief was made and which I declined to decide saying that the suit itself should be heard, that the entire contest was always about control. But the picture that gradually emerged, though some of this is common knowledge in Mumbai and India, began to show that this was, at some subliminal level, about something far weightier: it was about dominion over the entirety of a faith, all its adherents, their lives; and yes, about dominion over a staggering amount of money and wealth, the dimensions of which are difficult to discern.

10.

The claim is undoubtedly a civil claim, one that agitates a civil right. That this may have wider consequences to the faith is immaterial. Most emphatically, I was clear that I was not being asked to decide who of the two should more appropriately be the Dai. That would be purely a matter of faith. I was asked to decide which of the two had proved, in accordance with civil law, the claim to having been properly appointed following proven doctrine, as the 53rd Dai.

III A caution to the faithful - and their lawyers

11. As the trial progressed, it became evident that, no matter what the outcome, I was presiding over a schism in the Dawood Bohra

faith. This is not the first schism is Shia Islam; but it is undoubtedly one I always wished had not happened.

12.

The faith runs deep. The split was not much spoken about, but it was clearly bitter. Families broke apart. The two camps were divided, even if their numbers were unequal.

13.

From the beginning, I made it clear to both sides that while the issues formally struck in the suit required an assessment of doctrine but also demanded proof of the rival narratives, I would not accept an assault on the character of the principal contestants. It was one thing to impeach credibility of the evidence of a witness. It is quite another to attribute sinister motives and worse to the opposite party. This interdiction on an attack on character just had to be done, for the schism had a physical manifestation in my court: those for the Plaintiff sat on one side, those for the Defendant on the other, and they kept a clear distance. Anything less restrained would have led to chaos and disorder in court. Above all, I stressed that I was conducting a civil trial about a claimed civil right, not a theological or religious one. The Evidence Act would rule, not emotion or sentiment or perception of doctrine.

14.

This was important because of a crucial aspect of the matter. The Defendant claimed to have been appointed more than once. The Plaintiff assailed each claim. But the last claim by the Defendant was at a time two years before the 52nd Dai's demise, when he was taken ill in London. From that time, and until his passing, the Plaintiff said, the 52nd Dai 'lacked the necessary capacity' to make a valid

appointment. This is more or less of a stripe of the kind of opposition one typically encounters in a contested testamentary action, where the allegation is that the testator lacked the necessary 'capacity', meaning she or he was too ill and too infirm physically and of insufficiently sound mind, memory and understanding to know what she or he was doing. This was accompanied by a case that the Defendant exercised what I can only describe as 'undue influence' on the 52nd Dai. Now had this been a case of an ordinary testator, there would have been no difficulty in assessing this challenge on the merits of the evidence led. But no Dai is in any sense 'ordinary', at least not in the faith. He is regarded as the Imam's representative on earth, an aspect I outline in the next section, and is considered to be infallible. In particular, his choice of successor, the Plaintiff himself said, could not be questioned - nor revoked, altered or changed. It was divinely ordained, and known by divine inspiration to the Dai and to the Dai alone.

15. This presented an immediate conflict. On the one hand, there was the acceptance of infallibility. And yet the Plaintiff had to navigate this course of maintaining that the 52nd Dai (at the relevant time, during his hospitalization in London and after) was not infallible. To the contrary: he was so enfeebled and so fallible that he knew not what he was doing. It was the Defendant, not an Imam and not Allah, that guided the 52nd Dai's hand. Self-evidently, for a faith with such belief, this is potentially explosive, even leaving aside any logical, moral and theological conundrums it presented. After all, how could the Plaintiff, who claimed succession from the 52nd Dai, and who said he was infallible, and his choice was by divine inspiration of something divinely ordained, also maintain that the

52nd Dai was under compulsion and lacking the necessary mental capacity to know what he was doing? On the question of infallibility of choice, indeed, I myself once put a question to the present Plaintiff. I asked what was to happen if a Dai's chosen successor died or became incapacitated or suffered some disability that prevented him from functioning normally? The answer by the Plaintiff was that this could never happen, because the Dai was infallible and his choice, being pre-ordained and divinely communicated, could not be wrong. A chosen successor may pass away before he takes the mantle of a Dai, and a Dai himself might fall ill, but a chosen successor could never be incapacitated.

16.

Seeing all this, more than once I asked counsel to find a way to balance the demands of the case against further commentary, and not to carry the matter to a higher pitch. All counsel agreed at once, and the cross-examination and the arguments were appropriately moderated, even muted. Those who were not directly engaged in instructing solicitors or counsel but came to attend the proceedings understood and were, too, throughout sober and restrained. The surface at least remained calm, never once being allowed to be disrupted by the turbulence beneath. I must appreciate this conduct of all at the beginning of this judgment; it made my task easier (and allowed for moments of shared lightness and levity).

17.

I follow suit. I have refused to comment on the persona, let alone the character and qualities, of either the Plaintiff or the Defendant. I have limited myself to what I believed, and still believe, to be the sole concern of any civil trial court anywhere - matters of proof.

IV The lawyers and the support team

18.

The legal arsenal on display was formidable by any measure. On each side, there was an army of assistants and juniors. After a brief dalliance with a senior counsel, Mr Desai led for the Plaintiff, assisted by Mr Mody, Mr Kohil, Mr Shukla, Ms Shah and Ms Khanwilkar. From the beginning, Mr Desai clearly knew what he was up against, and the mountain he had to climb.

19.

On the other side, for the Defendant, Mr Chagla led the charge for the Defendant and was present throughout until 2020 and Covid. His mainstay was clearly Mr DeVitre, who seemed somewhere along the way to acquire a discernible proficiency in Arabic (while also putting on display his romance with the Oxford comma). Until the final hearing, Mr Dwarkadas was an occasional visitor on the Defendant's team. Mr Savant was present throughout to assist. Mr Pooniwala somehow managed to keep all the seniors on track. Relegated to the second row was Ms Irani, a sedulous keeper and tracker of documents in evidence, their complex and bewildering numbering and more, never once wrong in calling the correct number. And there was the rest of the team behind them. We lost far too much time in Covid. When Mr Chagla encountered some health issues, Mr DeVitre took over, especially during the cross-examination before the Commissioner and final arguments. He and Mr Dwarkadas divided the submissions between themselves.

20.

The assistance on both sides has been exceptional. My thanks to every single lawyer before me.

The structure of this judgment

21.

This judgment is probably shorter than expected, but longer than I wished. I have not structured it conventionally. There are at least three departures from accepted practice in deciding suits. First, after this introduction, I have attempted a short history (or is it biography?) - unbidden, I might add - of the Dawood Bohra community (not intended to be authoritative, culled from different sources including ones on record, and avoiding discussion of divergences). I came to this late, and on my own, but believed it to be necessary for a clearer understanding of the origins of the faith and why this suit was so bitterly contested.

22.

I have then proceeded to summarize the plaint and written statements (there was a second one after the plaint was amended), proceeded to the issues.

23.

After this comes my second departure from convention: a separate section on the Evidence Act, some of its provisions, a general assessment of the approach and other governing legal principles. Again, this has a selfish interest. Once the general principles were set out, I had to then assess the evidence against those principles. This made it simpler, easier and shorter than the alternative, which was to take every single nugget and put it under an evidentiary microscope. After all, this is a civil trial, not a criminal one. I have to assess, as I will discuss, likelihoods and probabilities - and the preponderance of probabilities. There are overarching principles that govern civil trials, and I will visit some of these

(including relating to hearsay, inferences, probative burdens, presumptions and expert testimony) in this section.

24.

It is the Evidence Act that must be my guide throughout; nothing short of it will do. When we see what it says, it will become clear that in a civil trial it is the overall assessment of the evidence that matters.

25.

I have then gone on to a very brief overview of the evidence, only to identify those who gave testimony.

26.

After this, I have proceeded conventionally, taking the issues in the manner I thought most appropriate. Then there follows the final order, which is this: I have dismissed the suit.

27.

'Islam': submission to the will of God. This monotheistic religion, one of the three Abrahamic religious groups with Judaism and Christianity, centres on the Quran and the teachings of Muhammad, the acknowledged founder; held to be not just a prophet, but the Prophet.

28.

It is probably fair to say that the history of Islam is a story of schisms. These began immediately after Muhammad, when the faith split into the Sunnis, today the largest denominational group, and the Shias. The differentiation is crucial to an understanding of what follows in relation to the Dawoodi Bohras. Sunnis believe that the first four Caliphs were Muhammad's rightful successors. The Shias, the second largest group, split with the Sunnis over the issue of Muhammad's successors - and succession, as we shall see, is central to this case.

29.

A turning point in Islamic history is the event at Ghadir Khumm, on Muhammad's return from his last pilgrimage to Mecca. It is here, at Ghadir Khumm, that Muhammad is said to have appointed his cousin (and son-in-law), Ali as his successor, and bade his flock follow Ali. There is a statement about wills, testaments, authority, but the Shias all hold that Ali was Muhammad's successor and - this is important - the next Imam, or spiritual and political leader after him.

30.

In the Shia branch, the 'Twelvers', also I believe called the Ithna or Isna Ashari, are the largest. While some of the first Imams are commonly revered in Shia Islam, the Twelvers believe in the first twelve, the last of whom is said to have gone into occultation, to return one day as the Mahdi. An 'occultation' occurs when one object is hidden from view by another that passes between the viewer and the object (not to be confused with an eclipse, which is the casting of a shadow). An occultation is a blocking from view - a distant object is obscured by one closer. In Shia Islam, this is an eschatological belief: the Mahdi, a descendant of the prophet Muhammad, has been born, and was concealed; but he will re-emerge on the day of judgment (or the end of time) to establish or re-establish justice and peace on earth. The Twelvers believe that the 12th Imam to be in occultation.

31.

The Shia belief in Ali's succession directly developed into the concept of the Imamate, the credo that Muhammad's descendants and Ali's bloodline are the rightful leaders or Imams of Islam. Within the Shia group, there are other subsects, including, for our purposes, the Isma'ilis.

32.

Another historical event key to Shia Islam is the Battle of Karbala, fought on 10th October 680 AD. The Umayyad Caliphate had nominated a successor. This was contested by the sons of some of Muhammad's followers, including Muhammad's grandson, Husayn (Ali's son). Husayn refused to pledge allegiance to the appointed Caliph successor. He travelled to Mecca. En route to Kufa, an garrison town in Iraq, Husayn's caravan, which had about 70 men, was intercepted by the Caliph's much larger 1000-strong force.

Husayn was forced to turn north. He camped on the plain of Karbala. On 2nd October 680, a larger Caliphate force arrived. The local governor refused Husayn safe passage unless Husayn submitted to his authority. Husayn refused. Battle was joined on 10th October 680. By all accounts, it was a massacre. Husayn and most of his relatives were killed. His surviving family was taken prisoner. This incident gave an impetus to the development of Shia Islam. Husayn's suffering and death are much written about (and taken as a historical tragedy in Sunni Islam as well). They are the subject of sermons to this day. His is said to symbolize a sacrifice in the battle of good over evil, right over wrong, justice and truth over injustice and falsehood. The battle itself is commemorated to this day every year during an annual ten-day period of mourning called Muharram.

33.

The Isma'ilis and Twelvers both accept the same first six Imams. The Isma'ilis broke from the Twelvers when they accepted Isma'il ibn Jafar al-Mubarak as the appointed successor to the sixth Imam of the Twelver branch of Shia Islam. The Twelvers believed the successor was Musa al-Kadhim, Isma'il's younger brother who was the successor.

34.

Between the 10th and 12th centuries CE, the Fatimid Caliphate, an Isma'ili Shia dynasty, controlled a vast area from the Mediterranean and Red Seas, covering parts of North Africa and West Asia. The dynasty traced its roots back to Muhammad's daughter, Fatima, and her husband Ali.

35.

Within Ismail'ism, further sub-sects came into being. At the time of the 19th Imam (around the 11th and 12th centuries CE), the Musta'li accepted al-Musta'li as the 19th Imam (and the ninth Caliph). The Nizaris held that the true successor as the 19th Imam was al-Musta'li's elder brother Nizar. The Musta'li branch began in Egypt - and the Dawoodi Bohras still have strong ties there - under the Fatimid Caliphate. It then moved to Yemen, which was the springboard for the advent of the group into western India. The Nizaris follow the Aga Khan; in parts of India and Pakistan, the Khojas are a predominantly Nizari Ismai'li community.

36.

The next split is the one in the Musta'li branch, at the time of the death of the 20th Imam, around 1131 or 1132 CE. His infant son, Abu.l-Qasim al-T.ayyib ibn al-Amir, was appointed the 21st Imam. The 20th Imam was assassinated (1130 CE).

37.

At this point, there enters the narrative one of the most remarkable personalities in the history: Queen Arwa al-Sulayhi. She is said to have been the only Muslim woman to have ever wielded both political and religious authority in her own right. She was the long-reigning rule of Yemen, initially along with her first two husbands, and then on her own from about 1067 CE until her death in 1138. She was conferred the prestigious title of Hujjah, which, in Ismai'li doctrine, meant that she was the living representative of the will of Allah. Popularly, she is known as Hurrat-ul-Malikah or Al-Hurrat ul-Malikah, or some variant, the Noble Queen. There were indeed other female monarchs. But only Queen Arwa (and her mother-in-law Asma) were, as monarchs in the Muslim world, to have had the

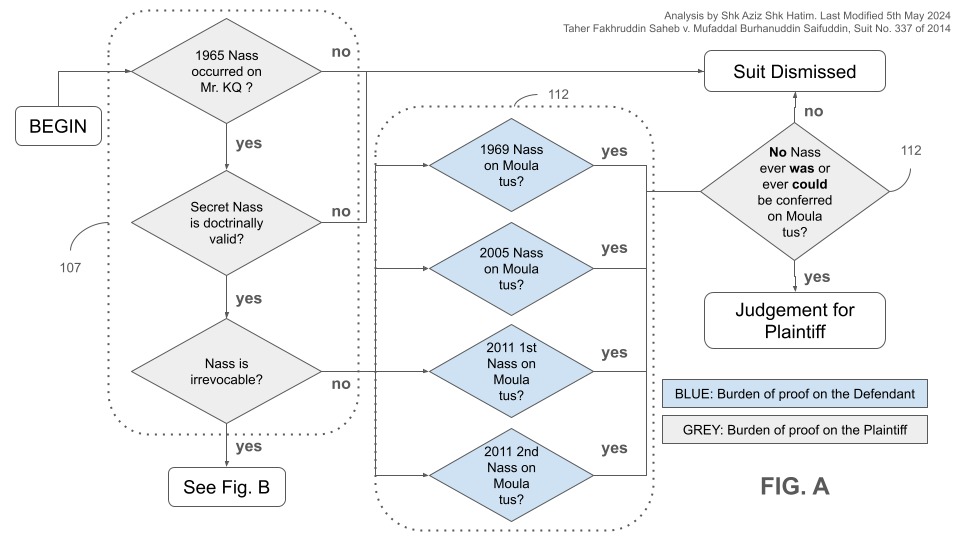

khutbah - a formal sermon event - proclaimed in their own names in mosques.

38.

Queen Arwa was in Yemen when the 20th Imam died. There is, in these records, reference to a communication or missive from the 20th Imam to Queen Arwa. He entrusted his infant son to her care. It is she who established in Yemen the office of the Da'i al-Mutlaq to act as the vice-regent of the 21st Imam while he was in occultation. Thus began the succession line of the Dai. Zoeb bin Musa was the first Dai. The present case is about the appointment of the 53rd Dai. They follow the son of the murdered 20th Imam - hence, Tayyibis.

39.

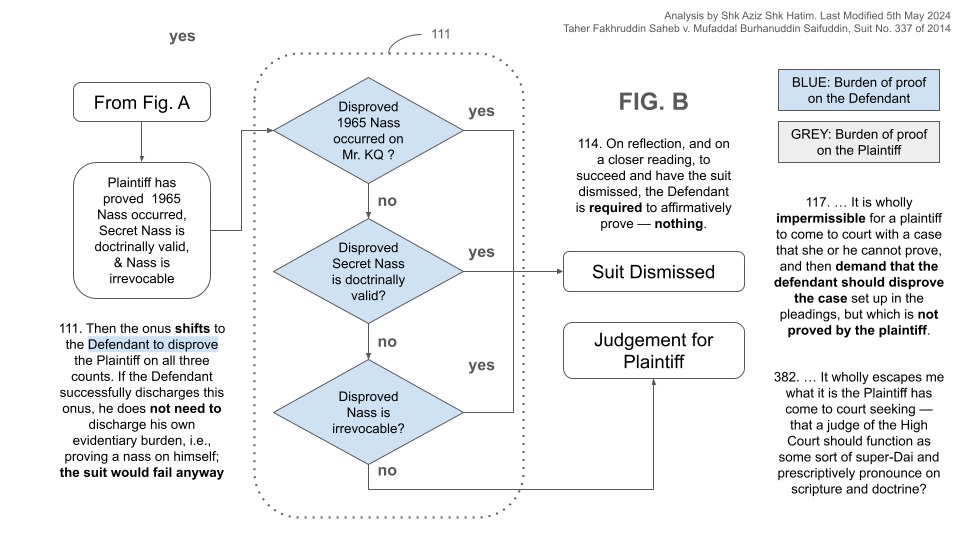

By now, the Musta'li Tayyibi had established a foothold through missionaries in western India, where there was initially the office of representative or caretaker to tend to the flock.

40.

This situation continued from the first to the 24th Dai (around the 16th century CE), with the Dais being in Yemen and appointing representatives in India. It was under the 25th Imam that the faith shifted to India.

41.

Now came the next split, this time in the Tayyibi group. It was about the succession as the 27th Dai, and the contest was between Dawood bin Qutubshah and Sulayman bin Hassan. Those who followed Dawood bin Qutubshah became the Dawoodis. The adherents of Sulayman became the Sulaymanis of Yemen. Sulayman claimed to have been appointed in writing by the 26th Dai, Dawood bin Ajabshah, of which writing Qutubshah was himself said to be the

scribe. Qutubshah claimed that Ajabshah had appointed him, not Sulayman. As we shall see, this discord is frequently referenced especially in regard to the mode, manner and tenets governing the appointment. A protesting Sulayman carried his plaint (a case of usurp; not much different from what is before me in this law suit) to court (that of the Emperor Akbar). In Lahore, and before he could reach the court, Sulayman died apparently from consuming a poisoned pickle. Akbar held for Qutubshah.

42.

In 1621 CE or so, a small faction separated regarding the succession after the death of the 28th Dai. The breakaway group became the much smaller Alavi Bohra community. There have been other factions: after the death of the 39th Dai in 1754 CE; and after the death of the 46th Dai in 1840 CE (a group that itself splintered in two).

43.

Thus, the Dawoodi Bohras are Tayyibi Musta'li Ismai'li Shias. They are governed by Fatemi or Fatemid law. The word Bohra appears to have nothing at all to do with Islam or any of these sub-sects, but is rather a reference to the primary or traditional occupation of a trading community.

44.

A fundamental tenet is the belief in the existence of the Imam on earth. He is occultation, and his work is done by the Dai. Critical to the survival of the faith is succession to the office of the Dai. This happens through what is called a nass, each Dai appointing his successor. 'Nass' is an Arabic word. It has many meanings in translation, and there was some expert testimony on this. It may mean

a known, clear and legally binding injunction or mandate, a divine decree, a designation, a nomination, a testament or will, or some form of a theological imperative. Among the Dawoodi Bohras, the pronouncement of a nass is, above all, a solemn and sacred duty of each Dai. He must appoint a successor. The choice is his, but it seems to be commonly accepted that it is divinely inspired. There was an argument by the Plaintiff that it is pre-ordained, which is to say that the Dai has little choice but to pronounce that which has been determined for him.

45. At the heart of the contest in this case lie two fundamental questions: First, how is a nass properly made? And second, once made

- that is to say, if shown to have been made - can it ever be retracted, changed or altered, or is it forever immutable? These are questions of doctrine, but they directly speak to the frame of the suit, for it is the Original Plaintiff's case that he was first so anointed by a proper nass, and any later pronouncement was ineffective. In answer, the Defendant says two things: First, on facts, that there was no nass conferred on the Original Plaintiff at all at any time; and, second, that even if there was, it could always be changed; and the last nass - the one at the time of the Dai's passing - would be the only one that governs.

46. As we have seen, the history of the Dawoodi Bohra faith is a tale precisely of recurring wars of succession. That succession is crucial is undeniable: he who succeeds controls everything and everyone. Some of the stories are tragic, and the battles bitter. There were assassinations aplenty. There was Sulayman and the poisoned pickle. The Emperor Aurangzeb also imprisoned not one, but two,

and their travails are spoke of to this day. Other stories are altogether more Rabelasian. There is one, for instance, of the two sons of an Imam bickering about who would be the successor. Along came the father and figuratively smacked their heads together. "The true Imam," he said, "is yet to be born…"; and the text tells us that as he said this the 18th Imam pointed to his 'blessed loins'.

47.

The Dawoodi Bohras are nothing if not the most assiduous chroniclers. They document and record everything. There are many Dawoodi Bohras in our profession, but even within the most private places, there seems to be an emphasis on documentation, record-keeping and some degree of formality to these documents (whether or not the formality comports with law is another matter). As we shall see almost immediately, this documentation and record-keeping - or, more accurately, the lack of it - is a crucial facet of the affirmative case on either side. Specifically, the Defendant has never failed to point out that the Plaintiff has no record at all of his claim, and that this is in direct contrast to the voluminous documentation of the Defendant's claim.

48.

Some of the language is difficult to navigate, even in accepted translation. It is much given to excessive hyperbole. To call it flowery is an understatement. Sometimes, it seems that an entire Mughal garden has been dragged into a single thought. The most delectable Indianism shrivels in comparison to, say, 'the coolness of my eye'. Much of it is self-referential or elliptical, or both; and to parse a strand of theologically sound doctrine or tenet from this is no easy task. The discourses are also not just textual. Vast amounts are in the form of sermons, words spoken, and these - the Dawoodi Bohras being

incorrigible annalists - are dutifully recorded (again with the best of equipment, all self-operated). The 'best' sermons are by the most 'learned', and the quality of the sermons is taken as an indicator of doctrinal learning and wisdom. These sermons have certain set elements. Recounting of historical incidents is one key feature, and is used to lay out a path to proper conduct. Sometimes, it takes the form of a parable. Of necessity, past incidents are, like all history, subject to interpretation - and this, too, has been the focus of much contestation in the trial. Another key element is grief. A good sermon must be able to convey profound sorrow and grief. Typically, the sermon-giver will expound on a tragic past incident, sometimes one of several centuries earlier; and then, expressing sorrow and grief, will turn his face into a fine white handkerchief and sob audibly. At this, the entire congregation will burst into a sympathetic wail. Used as we are to canned laughter on television sitcoms, watching a video of such a sermon can therefore be more than somewhat discombobulating. But the point, I think, is more straightforward: it is a preoccupation, perhaps even an obsession, with the past; and in a concept familiar to those of us in law, of following precedent as a prescription for a life according to the faith.

49. Today the Dawoodi Bohras number over one million across 40 countries. They have a presence from China to the United States. As a community, they are known to be reasonably well-educated and literate, and engaged in trade, business, profession and entrepreneurship. Their garb is traditional and easily identifiable; their lifestyles are often very au courant, especially among the wealthier. Many traditions follow or adapt from Indian custom. There is an identifiable Bohri cuisine, the festive one of which that always

begins with ice cream (on the salutary principle, presumably, that if life is uncertain, one is well-advised to eat dessert first), progresses to a savoury, and then to the main meal. They have always had a pronounced partiality to sugary liquid concoctions, nowadays in the form of cola and flavoured soda drinks (including, I might add, at around 4 pm daily in a discreetly sleeved glass in my court in the middle of the Plaintiff's cross-examination, the pop-and-fizz quite unmistakable). Their dress is distinctive. Traditionally male attire is a predominantly white, three-piece outfit: tunic or kurta-like garment, a long overcoat and loose trousers with a embroidered white cap (that never comes off, even in court). Flowing beards are de rigeur (and are often stroked thoughtfully at critical junctures in a cross-examination). Ladies wear a two-piece dress called a rida, quite unlike a hijab, purdah or a chador. It can be of any colour except blank, has decorative designs and lace, and does not cover the face though there is a flap that can be pulled across the visage when desired.

50. The language is Lisan ul-Dawat, said to be a dialect of Gujarati. Many words and expressions and phrases are indeed liberally salted with Gujarati, but the vocabulary is also intensely Arabic, Urdu and Persian, written in a particular right-to-left style. In the community, there is a compulsory zakat or donation to a pooled fund - annually, this is vast. They have also kept abreast with technology; I doubt there was an electronic gadget in the market that did not find its way into the court, and sooner rather than later. There were incessant upgrades. In the city, and through a dedicated trust, the Dawoodi Bohras are undertaking a massive revamp and cluster re-development of one of the most congested wards. The Dawoodi Bohras are also builders - they build mosques and establish libraries everywhere

they have a presence. This traditional activity meets technology for they now have e-Jamaat cards that can track when and how often a member of the flock has (or has not) prayed. In Mumbai, the Syedna and close family live at Saifee (or Saify) Mahal at Alexander Graham Bell Road, Malabar Hill. This is, by all accounts, a complex of several floors and structures, interconnected yet with separate apartments, and some shared common facilities (such a community kitchen optionally available). The Syedna has his own residential and work quarters here. The Syedna is not confined to these premises. There is frequent travel both domestic and overseas (where, too, the Dawoodi Bohras own substantial properties and appear to be able to command first-rate hospital facilities without much heed to the regular rules applied to others).

51.

An overall impression is that this is a closely-woven community tied intimately to the faith, yet in matters mercantile fully integrated into society in various fields of endeavour, including banking, trading, manufacturing, architecture, engineering, medicine, accountancy and law. To be sure there is a reformist faction, but that has never attained a formal separation. For the rest, and until now, the community as a whole is literally steeped in Ismai'li Shia Islam, tracing its lineage all the way back to Gadir Khumm, Ali and the Prophet Muhammad. In the time since, Shia Islam and the Dawoodi Bohras themselves have suffered many splits and splinters and schisms.

52.

This is possibly the most recent.

53. From this point on, I refer to Khuzemabhai Qutbuddin as the "Original Plaintiff", and the successor Plaintiff, Taherbhai Qutbuddin, as"the Plaintiff".

The suit and its amendments

54.

Syedna Mohammed Burhanuddin Saheb ("Syedna Burhanuddin"), the 52nd Dai, died on 17th January 2014. He was the Dai from 1965. The Original Plaintiff sued on 28th March 2014. There was a first amendment in October 2014. The Original Plaintiff died in America on 30th March 2016. The Plaintiff sought impleadment in his stead; I allowed this amendment too, and the Plaintiff re-affirmed the Plaint on 18th March 2017.

55.

The plaint is not remarkable for its brevity or concision - and, as I later found, much of what it says is directed to the kind of prima facie case one would have to assess in an application for interim relief rather a pleading properly so called. As framed, it runs to 160 pages without the exhibits and not counting the insertions by amendment. It abandons every known canon and precept of a 'pleading', and includes evidence, arguments and submissions. My task has been to condense this to a fraction of that length, under 10 pages, discerning from it a statement only of facts according to the Plaintiff.

56. Much of the plaint reads like a written statement to the written statement, but that is because it was amended following filings in the Notice of Motion for interim relief.

The reliefs sought

57. The reliefs in the suit (after all amendments) are these.

(a)

that this Hon'ble Court be pleased to declare the Original Plaintiff was appointed as the 53rd Dai al-Mutlaq of the Dawoodi Bohra Community and that he was entitled to succeed as the 53rd Dai al-Mutlaq of the Dawoodi Bohra Community;

(a-1) That this Hon'ble Court be pleased to declare the Plaintiff was duly and validly appointed as the 54th Dai-al-Mutlaq of the Dawoodi Bohra Community by the Original Plaintiff and the Plaintiff is entitled to succeed as the 54th Dai-al-Mutlaq of the Dawoodi Bohra Community;

(b)

this Hon'ble Court be pleased to further order and declare that Original Plaintiff being the 53rd Dai al-Mutlaq of the Dawoodi Bohra Community was entitled and the Plaintiff being the 54th Dai al-Mutlaq of the Dawoodi Bohra Community is entitled to administer control and manage all the properties and assets of the Dawoodi Bohra Community including and not limited to community's wakfs and trusts, and assets / properties which have been presently usurped by the Defendant;

(c)

that the Defendant be ordered and directed to handover to the Plaintiff possession of the various movable properties which are more particularly described in Exhibit "SSS" hereto, which has been usurped by Defendant upon the death of the 52nd Dai al-Mutlaq;

(d)

that the Defendant be restrained by a permanent

order and injunction from in any manner holding himself out as or doing any acts, deeds or things as the Dai al-Mutlaq of the Dawoodi Bohra Community;

(e)

that the Defendant by himself, his servants and agents be restrained by a permanent order and injunction from in any manner preventing or obstructing the Plaintiff from carrying out his duties as the 54th Dai al-Mutlaq or in any manner threatening or taking any steps against members of the Community who believe in the Plaintiff;

(f)

that the Defendant, his servants and agents be restrained by a permanent order and injunction from in any manner preventing the Plaintiff from entering and using Saify Mahal situate at A.G. Bell Road, Malabar Hill, Mumbai 400006, which houses the official office-cum-residence of the Dai al-Mutlaq;

(g)

that the Defendant, his servants and agents be restrained by a permanent order and injunction from in any manner preventing the Plaintiff from entering and using Saifee Masjid, Raudat Tahera and all other Dawoodi Bohra community properties (such as mosques, Dar ul-Imarats, Community halls, mausoleums, schools, colleges, hospital, maternity homes, musafirkhanas, cemeteries, offices, etc.) more particularly described at Exhibit "III" hereto to conduct audiences, prayers, sermons, etc.;

(h)

that the Defendant, his servants and agents be restrained by a permanent order and injunction from in any manner using, selling, destroying, interfering with or exercising any rights over the Dawoodi Bohra Community's wakfs and trusts, and assets / properties to which the Dai-al-Mutlaq is entitled by virtue of his office;

(i)

that the Defendant be directed to furnish to the Plaintiff complete particulars of the assets / properties to which the Dai-al-Mutlaq is entitled by virtue of his office, including the database of all the Dawoodi Bohra community

members (ejamaat ITS database) and hand over such assets / properties to the Plaintiff;

(j) that the Defendant be ordered and directed to furnish to the Plaintiff complete particulars of the funds and assets / properties of the trusts, wakfs and assets / properties associated with the office of Dai al-Mutlaq utilised or disposed off or dealt with by him, or under his direction or acquiescence since 4th June 2011 and bring back and deliver such funds and assets / properties to the Plaintiff;

III The parties

58.

The Original Plaintiff and the 52nd Dai, Syedna Burhanuddin, were brothers. The 51st Dai had twelve sons by four wives. The Original Plaintiff was the eleventh; Syedna Burhanuddin was the eldest.

59.

The Defendant is the second son of the 52nd Dai, Syedna Burhanuddin. He is also married to the daughter of the 51st Dai's fourth son, Yusuf Bhaisaheb, which would make the Defendant the nephew of the Original Plaintiff. The Defendant was also once married to the Original Plaintiff's daughter and, therefore, was the Original Plaintiff's son-in-law. The present Plaintiff is the Original Plaintiff's son. This means that the Plaintiff and the Defendant are first cousins, the sons of two brothers.

IV The 160-page plaint in nine paragraphs

60. The Original Plaintiff's case is in two parts. The first is about his own nomination or appointment, and has it own time-line. The

second is an effort to dislodge the Defendant's case. Discarding argumentation and evidence, and condensing the factual narrative, the Original Plaintiff's case comes to this:

(i)

On 10th December 1965, the 52nd Dai appointed the Original Plaintiff as his Mazoon (one of the highest ranks, said to be the second highest position in the faith; the third rank is the Mukasir), and while doing so at Saifee Masjid, Bhendi Bazaar at the 52nd Dai's pledge of allegiance (misaaq majlis) said some words to the congregation. This, the Original Plaintiff said, made persons of higher spiritual learning that the 52nd Dai had conferred a nass of succession on the Original Plaintiff. At that time, the 52nd Dai was 51 years old and the Original Plaintiff was 25.

(ii)

Returning to Saify Mahal (en route making another statement), the 52nd Dai and the Original Plaintiff repaired to the 52nd Dai's private apartments. They were the only two there. The Original Plaintiff understood that he had been appointed a successor. There was no other person present. There was no public announcement of this - at any time. It was 'understood' that this was also the appointment of a Mansoos (successor). The Original Plaintiff said that this was consistent with the wishes of the previous Dai, the 51st Dai. The 52nd Dai gave the Original Plaintiff a finger ring and told him (in private, and orally) that the Original Plaintiff would be the 53rd Dai. The Original

Plaintiff was asked not to reveal this and to hold it in confidence. He did. Later, when asked why he had not publicly announced it, the 52nd Dai apparently said that had he done so, 'swords would have been drawn' - used to bolster that others knew of the Original Plaintiff's appointment, and, too, that had this been disclosed, the Original Plaintiff's life would have been in danger.

(iii) Others, including the Defendant, then paid homage to the Original Plaintiff (offered sajda). This went on for three decades. The Original Plaintiff led all prayers and generally enjoyed high regard and esteem in the community. Many referred to him as 'Maula'. Documents refer to him as holding a high rank and enjoying attendant respect.

(iv)

Then the Defendant and his 'coterie', a word with which the plaint is liberally peppered, hatched a plot against the Original Plaintiff to malign him in furtherance of a 'devious scheme'.

(v)

No nass could have been conferred on the Defendant at any time. It could not have been done on 4th June 2011 at the Bupa Cromwell Hospital in London, because the 52nd Dai had just suffered a stroke. There could not have been an earlier nass (including the one of 1969 claimed by the Defendant) or a later one, because a nass

once pronounced is irrevocable - and therefore the nass on the Original Plaintiff would govern. Any nass claimed by the Defendant after 4th June 2011 (specifically, on 18th August 2011) is a fabrication; including the later mention by the Defendant of a diary (of which much more later).

(vi) The Defendant is an unworthy candidate for succession as a Dai.

(vii) The Defendant mounted a hate campaign against the Original Plaintiff and being jealous of the Original Plaintiff, usurped the succession.

(viii) The Original Plaintiff was silent, in fealty to the 52nd Dai's wishes, about the nass conferred on him in 1965 throughout the rest of the 52nd Dai's lifetime after the illness in 2011, a period of nearly two and half years - even after the announcement of the Defendant's appointment in 2011 - right until after the 52nd Dai's demise. The Original Plaintiff hoped that the 52nd Dai's health would improve and that he would 'set right the falsehood perpetrated by the Defendant'. The Original Plaintiff feared for the well-being of the 52nd Dai. He did not participate in all but one event where the Defendant presided.

(ix) It was only on 18th January 2014, the day after the 52nd Dai passed away, the Original Plaintiff publicly announced the nass that had been conferred on him in December 1965.

61.

The rest is evidence, argumentation and submissions. It is not necessary to summarize or set out every chunk of supporting evidence.

62.

Two things stand out in any reading of the plaint:

(i)

There is no witness other than the Original Plaintiff to the 10th December 1965 nass;

(ii)

That nass of 1965 was not revealed explicitly until after the 52nd Dai died, by which time the Defendant had already been proclaimed as the one on whom a nass was conferred by the 52nd Dai.

The plaintiff's case regarding a nass of succession, generally

63. As this is crucial to the Plaintiff's case, it is best to summarize the Plaintiff's case on the requirements of a valid nass of succession. The case is set out in a negative form, in the sense that it delineates what is not required, rather than attempt to provide affirmative or positive boundaries. As I understood it, the only positive aspect was that there ought to be some communication in some form, explicit or implicit, of succession.

64.

The entirety of the case is hinged on the solitary nass pronouncement of 10th December 1965, at a time when the Original Plaintiff and the 52nd Dai were alone together.

65.

First, the factual:

(i)

On 10th December 1965, the 52nd Dai conferred nass on the Original Plaintiff.

(ii)

This was in private. No one else was present. There were no witnesses. The conferment was oral.

(iii) No one was ever told.

(iv)

The 52nd Dai told the Original Plaintiff not to reveal the nass, and the Original Plaintiff abided by this injunction until after the 52nd Dai died.

(v)

At Saify Masjid in December 1965, the words of the 52nd Dai were sufficient indication to those of higher learning that such a nass had been conferred.

(vi)

Even if no one was told, everyone knew of the nass. Therefore, though formally appointed as the Mazoon - the second highest rank - the Original Plaintiff received respect and honour due to a Mansoos, the chosen or anointed successor.

(vii) There is no reason to disbelieve the Original Plaintiff's word since he held the position of Mazoon, unchallenged and unchanged, for half a century.

(viii) Factually, no nass was ever conferred on the Defendant at any time.

66. Next, the doctrinal, according to the Plaintiff:

(i)

No witness is ever needed for a nass. The one who pronounces or the one on whom it is pronounced are sufficient and may be deemed to be witnesses, if witnesses are needed;

(ii)

Once conferred, a nass is irrevocable. It is pre-ordained and divinely inspired. The Almighty does not err.

(iii) Therefore, the 52nd Dai could not have ever conferred a nass on anyone else, whether the Defendant or some other person.

67. This is the case the Original Plaintiff brought to court.

The first written statement

68. The first written statement seems to take the length of the plaint as a challenge to be met: it runs to five volumes pages with annexures, 1018 pages. The written statement itself is 187 pages. The traverse of the plaint's paragraphs does not begin until page 75. In this summation, I am, of course, ignoring the annexures. Paragraph 6 at page 5 serves up this delectable morsel, entirely forgetting the goose, the gander and the sauce:

The Plaint is prolix and argumentative and incorrectly includes alleged evidence sought to be relied upon.

(1) Preliminary Objections

69. The Defendant raises preliminary objections:

(i)

That this court does not have jurisdiction because the suit is one for a declaration regarding religious privileges and positions, and is therefore not a civil suit.

(ii)

That the suit seeks orders in respect of immovable properties and is therefore a suit for land. Since many of these properties are outside the territorial jurisdiction of this Court on its Original Side, and, in any event, without leave under Clause 12 of the Letters Patent, this Court lacks jurisdiction.

(iii) The suit seeks relief in regard to community trusts, many of which are registered under the Maharashtra Public Trusts Act, 1950 and, for those outside the State, under the laws of the states in which they are registered. Change reports have been filed showing the Defendant as the sole trustee. Therefore, the suit is barred, and in any event, needed the written consent of the Charity Commissioner.

(2) The Defendant's affirmative case

70. The Defendant begins by setting out his affirmative case. This is remarkable for one thing above all: the Defendant's claim that he was repeatedly anointed the 52nd Dai's successor. He lays claim to four separate pronouncements of nass on distinct dates/at distinct times and in differing contexts:

(i) 28th January 1969; (ii) In 2005;

(iii) On 4th June 2011 at the Bupa Cromwell Hospital in London;

(iv) On 20th June 2011, in Mumbai.

71. The first two were private. The third and fourth were public - and to the knowledge of the Original Plaintiff and the Plaintiff. The 4th June 2011 nass was later recorded in writing in a notarized document of 2012 and in a Power of Attorney of 2013. Each of these is detailed later in the written statement.

72.

From 2011 and until the 52nd Dai passed in January 2014, i.e., for two and a half years, the Defendant functioned as the successor apparent. He was so acknowledged by the entire community - including the Original Plaintiff.

73.

After the 52nd Dai's demise, except for the Original Plaintiff, the Plaintiff and few others, the entire community recognized, acknowledged and accepted the Defendant as the 53rd Dai.

(3) On the requirement of a valid nass

74. According to the Defendant, the essential requirements of valid nass of succession are these:

(i)

It must be conferred in the presence of at least two witnesses;

(ii)

A nass is freely alterable and revocable. It can be changed in the next instant.

(iii) It is the last nass, at the time of the last drawn breath of the incumbent, that supersedes all and any previous nass;

(iv) The incumbent Dai has the sole prerogative to choose his successor. His choice is not trammelled by the views of his own predecessor.

(4) The Defendant's first claimed nass of 1969: the Champion notebook and after

75. On 28th January 1969, Syedna Burhanuddin was to take a morning flight out of Mumbai for his Hajj pilgrimage to Mecca and Medina. At about 1 am, he summoned three persons to his private chambers on the 1st floor of Saifee Mahal. He conferred nass of the Defendant. The three were witnesses. The Defendant was not told at that time. One of the three, one Yamani, the 52nd Dai's personal secretary, recorded this in writing (in Lisan al-Dawat) in 'a small red notebook which bears the name CHAMPION note book' on its cover. Champion is evidently the brand, not a description of the contents or the author. The 52nd Dai is said to have signed this and made an inscription in his own hand. The 52nd Dai kept the Champion notebook. Yamani was apparently a chronicler and noted this in his own journals. The Defendant learnt of the Champion notebook in 2009, when the 52nd Dai himself showed it to the Defendant. It remained in the 52nd Dai's cupboard until his demise. Another witness, one Tambawala, apparently also made a contemporaneous record in a calendar diary, kept with confidential papers relating to a business enterprise. That diary notes further that the 52nd Dai's flight was delayed to the evening. Tambawala's son found this calendar diary and gave it to the Defendant's brother, Qaidjoher Ezzuddin (the 52nd Dai's eldest son) around 6th February 2014. The Defendant read the Champion notebook entry in public on 4th February 2014 after the 52nd Dai had passed away. He held it up for all to see. This was dutifully videographed. It is also alleged that in 1994, the 52nd Dai mentioned the 1969 nass to Yamani's son, Abdulhusain, who had by then become the personal secretary, and which he noted in a separate book. Abdulhusain in turn gave the book to Qaidjoher. Everyone was asked to keep it confidential - even though very many people clearly knew.

(5) The Defendant's second claimed nass of 2005

76. This is said to have happened in November 2005. The 52nd Dai called two of his sons, Qaidjoher and Malekulashter Shujauddin, to his residence at Bonham House, Ladbroke Road (just off Kensington and Holland Park) in London. Apparently, the 52nd Dai asked both to 'bear witness' that he had conferred nass on the Defendant. The 52nd Dai mentioned the 1969 nass. The two were witnesses. He swore both to secrecy. Qaidjoher disclosed this to the Defendant and other family members, on 4th June 2011 in London after the 52nd Dai had publicly conferred nass on the Defendant.

(6) The Defendant's third claimed nass of 4th June 2011

77. The 52nd Dai was again in London at Bonham House in June 2011. On 1st June 2011, he took ill and was admitted to the Bupa Cromwell Hospital, a short distance away. A mild stroke was later detected. He was attended to by many medical professionals. He was not comatose. He continued his daily routine, after a fashion, praying (first from the bed and then in a chair), reciting the Qu'ran and so on. The 52nd Dai was said to be alert and intelligible in speech, though enfeebled. His children visited him. On 4th June 2011 at about 6:30 or 7 pm, three of his sons were visiting them. They sought his permission to leave. He bade them stay. His daughter was in the adjoining them. There were others, including the 52nd Dai's grandson. Then, seated upright on the bed, he summoned his daughter. He asked them to sit. At about 8 pm, in a weak voice the 52nd Dai began to speak in an oratorial style. Sensing something important in the offing, one of those present asked his son to start

recording on his cellphone. The 52nd Dai mentioned the Defendant by name four times and twice said "to the rank of Dai al-Mutlaq". He said, "we are appointing Mufaddalbhai to the rank of Dai al-Mutlaq," and then added "inform everyone." Then the 52nd Dai asked for sherbet. The three sons, daughter and grandson repaired to Bonham House. On the way, they asked Qaidjoher to join them there. At Bonham House, they informed Qaidjoher. After some delay, they told the Defendant of what had transpired. This is when Qaidjoher is said to have told everyone of the 2005 nass.

78.

The 4th June 2011 nass claimed by the Defendant was announced on 5th June 2011 by Qaidjoher at a majlis in London before a congregation of 2000 or so. An audio-recording was played at all Dawoodi Bohra centres worldwide, including India. There was a video recording as well.

79.

In India, the audio recording was played at a majlis at Saifee Masjid on 6th June 2011. The Original Plaintiff presided at this majlis. The Defendant claims that the Original Plaintiff thus accepted the Defendant's succession. He also claims that on 7th June 2011, the Original Plaintiff called Qaidjoher and congratulated him on the Defendant's succession.

80.

The 52nd Dai was brought back to Mumbai on 17th/18th June 2011 and taken directly to Saifee Hospital.

(7) The Defendant's fourth claimed nass of 20th June 2011

81. 20th June 2011 was the death anniversary of the 51st Dai. The 52nd Dai visited Raudat Tahera an austere mausoleum to pay homage. There was a majlis. The Original Plaintiff was not present. There is a long narrative, virtually minute-by-minute, in the written statement, but the point being made is that the 52nd Dai called the Defendant close to him and appointed him to the rank of Dai al-Mutlaq in public. He did so repeatedly and explicitly used the word 'nass'. There was live broadcast of the entire event. A video recording was later broadcast too.

(8) Reaffirmations

82. The Defendant claims that the 4th June 2011 nass was re-affirmed in a notarised document of 2nd March 2012 and is reflected in a Power of Attorney dated 18th March 2013 that the 52nd Dai executed and then had registered with the Sub-Registrar of Assurances.

(9) Case on 'conduct'

83.

Several paragraphs are devoted to the 'conduct' of the Defendant, viz., his assumption of authority and the acknowledgement of this by people in the faith.

84.

This is an ancillary argument inviting an inference. We are not really concerned with this, for what is at issue is whether, on facts, the conferment of a nass was proved on both sides.

(10) The requirements of a nass

85.

The written statement then asserts that witnesses are necessary for a nass or there must be a public proclamation. This is a question of doctrine. Paragraph is piled on paragraph to adduce evidence.

86.

The question of fact asserted in paragraph 13.5 that over 900 years and 52 Dais, nass has always been in the presence of witnesses or by public proclamation.

87.

Then the written statement endeavours a rebuttal of the evidence set forth in the plaint. A parallel is drawn between Sulayman (he of the poisoned pickle) and the Original Plaintiff. There is a long evidentiary disquisition on this.

88.

Then, on further material, the pleading is that in doctrine, a nass can always be superseded. It is not irrevocable.

(11) Conduct of the Original Plaintiff before 2011

89. Paragraph 17 contains an important assertion of fact, viz., that though appointed to the second-highest rank of Mazoon, did not live up to expectations or the confidence reposed in him in that position. The Original Plaintiff did not accompany the 52nd Dai on many travels, did not participate in major projects and activities. Yet he continued as Mazoon.

90. Here there is mention of a particular incident in 1988 in Kenya. The Original Plaintiff was there for about five months. A dispute arose, allegedly, between the Original Plaintiff and a local community member. The Original Plaintiff allegedly accused that person of plotting to have the Original Plaintiff deported. The community member protested. The 52nd Dai went to Kenya in May 1989, after the Original Plaintiff had returned. He absolved the local member. But all this is narrated to do little more than point a finger at the Original Plaintiff as being unworthy; and this is carried further, as little more than an accusation, in paragraph 17.5.

(12) Conduct of the Original Plaintiff after 4th June 2011 and until 17th January 2014

91.

Paragraph 18 of the written statement makes a positive statement that the Original Plaintiff did nothing to assert his claim between 4th June 2011 and 17th January 2014, when the 52nd Dai passed away. He sought no clarification from the 52nd Dai in his own lifetime. He was aware of various events at which the Defendant's appointment was mentioned, and yet did nothing. He even participated and presided over one such.

92.

There is mention, too, that he telephone Qaidjoher and conveyed his congratulations on the Defendant's appointment.

93.

He said nothing and did nothing when the Defendant presided over a particular function and relegated the Original Plaintiff, though the Mazoon, and despite his claim to being the only true Mansoos, to secondary position.

94. Now this is not merely prejudicial, though it is certainly that. It is a series of factual assertions set out to invite an inference against the Original Plaintiff. Of course these would have to be proved; but the pleading was essential to support any cross-examination or a case in cross-examination or later arguments.

(13) Other matters

95.

There are other assertions too, such as the relative positions of the Mazoon and the Dai intended to dislodge the case and suggestion that as a Mazoon, and therefore in the second rank, the Original Plaintiff was destined to be the Mansoos.

96.

The Defendant also asserts that the Original Plaintiff did not, in fact, keep to his vow of silence and secrecy. Admittedly, he sought legal opinion from a jurist in the 52nd Dai's lifetime.

97.

These assertions all relate to conduct and they are directed to setting a foundation for the Defendant's case that the entirety of the Original Plaintiff's case is more than an afterthought. It is, according to the Defendant, very much a latter-day epiphany, an extremely expensive gamble, a ploy to wrest control and simply taking a chance.

(14) The rest of the written statement

98. The rest is the usual paragraph-by-paragraph traverse, with guarded denials and statements of disavowal.

II The Additional Written Statement

99. After the plaint was amended, following the Original Plaintiff's demise and the Plaintiff was impleaded, the Defendant filed an additional written statement. It too has mostly denials.

III The Affirmations of both written statements

100. Neither written statement is affirmed by the Defendant. Both are affirmed by QaidJoher, said to hold a Power of Attorney from the Defendant.

The Issues Framed

101.

Issues were struck on 15th September 2014; one issue was recast on 7th October 2014, and then Issue No 3 was split in two by an order of 3rd May.

102.

I reproduce the issues with my findings against each:

ISSUE ISSUE FINDING NO

1(a) Whether the suit is not maintainable for the reasons stated in paragraph 1 of the Written Statement? NO

(b) Whether this Court has no jurisdiction to entertain and try the suit or grant the reliefs prayed for as stated in the Written Statement? NO

(c) Whether the reliefs prayed for by the Plaintiff in prayers (b) and (h) are barred by the provisions of the Maharashtra Public Trusts Act, 1950 as stated in paragraph 3 of the Written Statement? NO

2. What are the requirements of a valid Nass as per the tenets of the faith? AS PER FINDINGS

3-A Whether the Plaintiff proves that a valid Nass was conferred/pronounced on him as stated in the Plaint? NO

ISSUE ISSUE FINDING NO

3-B If Issue No 3-A is answered in the affirmative, Does not then whether the Plaintiff proves that a valid arise Nass was conferred/pronounced on him as stated in the Plaint?

4.

Whether a Nass once conferred cannot be NOT retracted or revoked or changed or PROVED. superseded?

5.

Whether the Defendant proves that a valid Nass was conferred on him by the 52nd Dai:

(a)

On 28th January 1969 YES

(b)

In the year 2005 YES

(c)

On 4th June 2011 YES

(d)

On 20th June 2011 YES as stated in the written statement and if the answer to Issue 4 is in the negative, DOES NOT

then whether any Nass proved on the ARISE Defendant as above consequently amounts to a retraction or revocation or change or supersession of any Nass previously conferred on the Plaintiff by the 52nd Dai?

6. What Judgment and Decree? SUIT DISMISSED

Analysis of the Issues

103. Issues Nos 1(a), (b) and (c) are all worded in the negative, laying the burden of proving these issues on the Defendant.

104.

Issues Nos 2 and 4 are connected. The question of revocability must be answered along with the issue of the essential requirements of valid nass.

105.

The burden of proving Issue No 3-A is on the Plaintiff. If this fails, the suit fails. Issue No 3-B will not survive unless Issue No 3-A is answered in the affirmative. Further, Issue No 3-B also depends on the answer to Issues Nos 2 and 4 (the requirements of a valid nass).

106.

Issue No 5 is in two parts. The first deals with the affirmative case of the Defendant that he was appointed Mansoos four times. The second part ties to Issue No 4, the question of revocability. On reflection, it is awkwardly phrased for it arises if Issue No 4 is answered in the negative. But that issue is whether a nass, once conferred, cannot be retracted or revoked or changed or superseded. To answer this in the negative would be to hold that a nass can be retracted or revoked or changed or superseded. But the issue, as cast, also connects back to Issue No 3, for it asks whether the nass on the Defendant is a 'revocation' of the nass on the Original Plaintiff - positing that Issue No 3 is answered in the affirmative. But if Issue No 3 is answered in the negative, the second part of Issue No 5 cannot possibly arise - there is simply nothing to retract, revoke, change or supersede. Having answered Issue No 3 in the negative, therefore, I have held that the second part of Issue No 5 does not arise.

III What the Plaintiff/Original Plaintiff must prove

107. To succeed, the Plaintiff must-

(a)

Prove that there was, factually, a nass pronounced on the Original Plaintiff on 10th December 1965;

(b)

Prove that this nass need not have been made known, and that it is sufficient to prove circumstantially that it was understood to have been conferred by some persons or by a class of persons; and

(c)

Prove that a nass once pronounced is irrevocable.

108.

The burden of proof, never shifting, is on the Plaintiff.

109.

If (a) above is not proved (or is disproved), the suit fails.

110.

If all these three ingredients are proved, the Plaintiff does not have to disprove the case of the Defendant.

111.

Then the onus shifts to the Defendant to disprove the Plaintiff on all three counts. If the Defendant successfully discharges this onus, he does not need to discharge his own evidentiary burden, i.e., proving a nass on himself; the suit would fail anyway.

112.

In addition, if the Defendant proves that at least one nass was conferred on him, and also shows that a nass is revocable or alterable, the suit fails, unless the Plaintiff can show (the onus being back on him) that -

(a) Factually, no nass was ever conferred on the Defendant; and

(b) That no nass could have been conferred on the Defendant.

113. The burden on the Plaintiff is very high; and there was always a distinct possibility that the Defendant would lead no evidence at all.

IV What the Defendant must prove

114. On reflection, and on a closer reading, to succeed and have the suit dismissed, the Defendant is required to affirmatively prove - nothing. This is startling, given the pleadings, the evidence and the labour, but I maintain it is correct. That the Defendant has assumed an evidentiary burden is another matter; and since issues are framed I will, of course, address them. But this yet remains: what if the Defendant had set up no affirmative case of any nass on himself at all? Could the Defendant - as a litigation strategy - have rested with disproving the Plaintiff's case on facts and on doctrine, setting up no affirmative case of his own nass, and, at most, leading evidence only of experts on doctrine? I believe that was entirely possible. If the suit failed, and the Defendant did not 'prove' a single nass on himself, what might have been the possible result? The answer is that the community and its doctrine would answer that for itself, not needing any judicial determination whatsoever. Further, this would have obviated the need for the Defendant to lead the evidence of medical professionals in London and to offer them for cross-examination by the Plaintiff. Then the Plaintiff would have had to summon them, take their examination-in-chief in court and climb the very steep hill of

attempting to be allowed to cross-examine their own witnesses (plus encountering the jurisprudence that such a practice is deprecated).

115.

But the Defendant having assumed a burden, and a comparatively lighter one, he must prove, albeit without consequence any one nass conferred on him after 1965. Even one will do. All four do not have to be proved.

116.

The Defendant also does not have to prove that a nass is revocable, alterable or changeable. The burden lies on the Plaintiff that it is not, for that is the Plaintiff's pleading and case from the beginning - and it is central to the Plaintiff's case.

117.

Let me put it differently, to end this part. It is wholly impermissible for a plaintiff to come to court with a case that she or he cannot prove (as we shall see in the next section), and then demand that the defendant should disprove the case set up in the pleadings, but which is not proved by the plaintiff. The simplest example should suffice. In a given case, without setting up an affirmative case in the written statement (and possibly without filing a written statement at all), a defendant could yet successfully destroy a plaintiff's case by showing through cross-examination that it was not proved.

I Generally

118.

In the hurly-burly of endless dockets and briefs, pressing ad interim and interim applications, urgent writ petitions and such like, all of us - judges included - seldom have the time to return to the fundamentals of civil law. Some facet of civil procedure at least is often addressed. But a deeper engagement with that astonishing achievement of codification, the Indian Evidence Act, 1872 seldom comes. For all the technology on display, in this matter it was my good fortune to be greatly assisted by lawyers some distance removed from the quick-fix internet-driven answers of narrow and targeted research. As I said at the beginning, I was also fortunate to be able to actually conduct the trial, itself a rarity, though one that got interrupted briefly by roster changes.

119.

It is important, I think, before I embark on an assessment of the evidence to set out the cardinal principles that must guide my hand. Apart from anything else, this will lend some brevity to the discussion that follows, for I will not need to constantly refer to these principles in detail at each stage.

II Civil Procedure

120. For our purposes, the discussion here is on two aspects: pleadings and 'cause of action'.

(1) Pleadings

121. Order VI, Rules 1 and 2 of the Code of Civil Procedure, 1908

("CPC") say this: Order VI Pleadings generally

1.

Pleading.-"Pleading" shall mean plaint or written statement.

2.

Pleading to state material facts and not evidence.-

(1) Every pleading shall contain, and contain only, a statement in a concise form of the material facts on which the party pleading relies for his claim or defence, as the case may be, but not the evidence by which they are to be proved.

(2)

Every pleading shall, when necessary, be divided into paragraphs, numbered consecutively, each allegation being, so far as is convenient, contained in a separate paragraph.

(3)

Dates, sums and numbers shall be expressed in a pleading in figures as well as in words.

(Emphasis added)

122. Clearly Order VI Rule 2(1) contains a proscription. It is expressed twice: "and contain only", and "but not the evidence by which they are to be proved." Yet, as we have seen the pleadings in this case have followed this only in the breach. Had the mandate been followed, the plaint was no more than a dozen pages. For instance, the correct pleading ought to have been:

"The Original Plaintiff's appointment as a Mansoos, the chosen successor to the 52nd Dai, was acknowledged and recognized by the community in various ways, including the

terms of address, paying homage of a special kind (performing sajda), and other positive acts."

The rest was a matter of evidence.

123. But among lawyers there is an instinctive terror of including too little (and, conversely, among judges of too much being brought in and needing to be read). This is undoubtedly because of the settled law that all evidence needs a 'foundation' in pleadings. No amount of evidence can be let in without a foundation in the pleadings. It is the plea that must be raised to sustain the introduction of evidence. I can do no better than to begin with the utterly marvellous single-paragraph decision of Viscount Dunedin J for the Privy Council in Siddik Mahomed Shah v Mt Saran & Ors. 1 This is the judgment (yes, the whole of it):

VISCOUNT DUNEDIN, J.:- This is a hopeless appeal. A certain Hote Khan is alleged by the appellant, who is in possession of certain lands which belonged to Hote Khan to have given these lands to him. That story is not accepted, and there are concurrent findings as to the fact by both Courts. After Hote Khan's death there was a transference of the lands in question by mutation of names effected upon the application of Hote Khan's widow. The Judicial Commissioners think it very probable that Hote Khan's widow being an ignorant person and with no one to help her, transferred the lands in that way in order that her spiritual adviser might hold them as trustee. The spiritual adviser, who is the appellant wishes to keep them first upon the ground already specified which their Lordships have already disposed of and, secondly upon the ground that it was a gift made by the widow herself but that claim was never made

1929 SCC OnLine PC 79 : 1930 PC 57 (1).

in the defence presented and the learned Judicial Commissioners therefore, very truly find that no amount of evidence can be looked into upon a plea which was never put forward. The result is that their Lordships will humbly advise His Majesty that the appeal should be dismissed. As the respondents have not appeared, there will be no order as to costs.

Appeal dismissed. (Emphasis added)

124. In Bondar Singh v Nihal Singh, 2 the Supreme Court said:

7. As regards the plea of sub-tenancy (shikmi) argued on behalf of the defendants by their learned counsel, first we may note that this plea was never taken in the written statement the way it has been put forth now. The written statement is totally vague and lacking in material particulars on this aspect. There is nothing to support this plea except some alleged revenue entries. It is settled law that in the absence of a plea no amount of evidence led in relation thereto can be looked into. Therefore, in the absence of a clear plea regarding sub-tenancy (shikmi), the defendants cannot be allowed to build up a case of sub-tenancy (shikmi). Had the defendants taken such a plea it would have found place as an issue in the suit. We have perused the issues framed in the suit. There is no issue on the point.

(Emphasis added)

125. In Regional Manager, SBI v Rakesh Kumar Tewari, 3 referencing both Siddik Mahomed Shah and Bondar Singh, the Supreme Court

2 (2003) 4 SCC 161. 3 (2006) 1 SCC 530.

said in paragraph 14 that leading evidence entailed laying a foundation for the case in pleadings. It no such plea is put forward, no amount of evidence can be looked into unless such a plea is raised.

126.

There is an unbroken line of authority on this principle: See: Ravinder Singh v Janmeja Singh, 4 in the context of an election petition, where, in paragraph 7, the Supreme Court said that it was an established proposition that no evidence could be led on a plea not raised in the pleadings, and that no amount of evidence an cure a defect in the pleadings. See also: Indian Smelting & Refining Co Ltd v Sarva Shramak Sangh, 5 Sarva Shramik Sanghatana v Director, Deccan Paper Mills Co Ltd, 6 Union Bank of India v Noor Dairy Farm & Ors, 7 Milind Anant Palse v Yojana Milind Palse. 8

127.

In this case, the problem is not one of paucity but rather the reverse, an over-abundance; and that the assertions are not 'pleadings' strictly speaking within the frame of the Code of Civil Procedure, 1908. The challenge was therefore to weed out that which was not a pleading. Given this, my approach was to be liberal in permitting questions in cross-examination and putting a case.

(2) Evidence Affidavits

4 (2000) 8 SCC 191. 5 2008 SCC OnLine Bom 1431. 6 2018 SCC OnLine Bom 2790. 7 1996 SCC OnLine Bom 571 : (1997) 3 Bom CR 126. 8 2014 SCC OnLine Bom 631.

128. The evidence in chief, in our CPC, is to come in the form of an affidavit.9 But here again, rather than 'evidence' as understood in the Evidence Act, one typically finds submissions and arguments. I had to weed out those portions that could not find place in the evidence affidavits. Some portions, it was argued, were 'hearsay'. I have dealt with this law a little later in this section.

(3) Cause of action

129. Fundamental to any civil action is its cause of action, an expression not defined in the CPC. In ABC Laminart (P) Ltd & Anr v AP Agencies, Salem, 10 possibly a locus classicus, the Supreme Court said:

12. A cause of action means every fact, which if traversed, it would be necessary for the plaintiff to prove in order to support his right to a judgment of the court. In other words, it is a bundle of facts which taken with the law applicable to them gives the plaintiff a right to relief against the defendant. It must include some act done by the defendant since in the absence of such an act no cause

of action can possibly accrue. It is not limited to the actual infringement of the right sued on but includes all the material facts on which it is founded. It does not comprise evidence necessary to prove such facts, but every fact necessary for the plaintiff to prove to enable him to obtain a decree. Everything which if not proved would give the defendant a right to immediate judgment must be part of the cause of action. But it has no relation whatever to the defence

9 Order XVIII, Rule 4. Nobody has ever reconciled Order XVIII Rule 4 with Section 1 of the Evidence Act, which says it shall not apply to 'affidavits'. 10 (1989) 2 SCC 163.

which may be set up by the defendant nor does it depend upon the character of the relief prayed for by the plaintiff.

(Emphasis added)

130.

This has been consistently accepted and reaffirmed: Church of Christ Charitable Trust etc v Ponniamman Educational Trust;11 Canara Bank v P Selathal & Ors;12 CK Ramaswamy v VK Senthil. 13

131.